Forlorn Soldier Monument Analysis

This slideshow features four of James G. Batterson’s earliest monument figures. This is part of my research on the Forlorn Soldier, a Civil War Monument that was never sold and has been on display at various locations in Hartford for over 100 years. Explanation for when the monument was created and why the monument was not sold is unclear. Some say it was rejected because of the positioning of the monuments feet. This slideshow, however, shows that other monuments created by Batterson, and his colleague Carl Conrads, had identical foot positioning and were sold just the same.

The Forlorn Soldier Monument features a man with a beard, which is consistent with the earliest two monuments featured here, one from Granby (1868) and the other from New Haven (1870). The Forlorn Soldier has two major inconsistencies from all of the monuments featured here. First, the arm positioning on the monuments here are above the belt and the Forlorn Soldiers arm is positioned below the belt. The other inconsistency is that all of these monuments have some sort of support on the back of the statue. The Forlorn Soldier does not have this same support.

CRELI Student Leader Communication Training

CRELI Student Leaders participated in an activity to develop their listening and communication skills. Watch as the students struggle to communicate and persevere through the challenge.

CRELI Summer Program

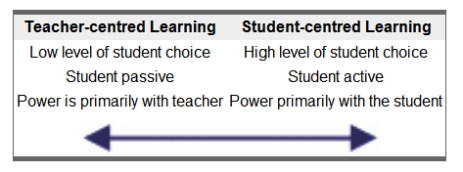

This summer I am running a program called Connecticut River Extended Learning Institute (CRELI). It is funded by a Nellie Mae grant and the focus is student-centered learning. This is my third year working as a teacher in this program, but this is the first year that I am a program manager. The theme for CRELI this summer is “honoring and sustaining diversity.” The students will work in small groups to create a product that fits this theme. Since the program is student-centered, the educators do not know what the final products will be or how they will be created. In many instances, this would be nerve-racking for educators, but through the process of this program, we will all learn how students at the center of the learning experience can be engaging, challenging and rewarding. Follow this blog to see how the program develops over the next two weeks.

Never-Ending Networking

Earlier this week, I was walking to my car following a meeting with an environmental scientist at Goodwin College and I realized that this process for researching the land use history is a never-ending series of connections and networking that takes me further and further down a rabbit hole. To use a driving simile, it’s like I am trying to get across Hartford during the Hartford Marathon. I am taking all sorts of side streets to get to my destination and some are dead ends while others bring me right back to where I started. Some, however, are accesses to wells of knowledge and interesting characters. This is how I felt after my meeting with Bruce Morton, director of the environmental studies program at Goodwin College.

Earlier this week, I was walking to my car following a meeting with an environmental scientist at Goodwin College and I realized that this process for researching the land use history is a never-ending series of connections and networking that takes me further and further down a rabbit hole. To use a driving simile, it’s like I am trying to get across Hartford during the Hartford Marathon. I am taking all sorts of side streets to get to my destination and some are dead ends while others bring me right back to where I started. Some, however, are accesses to wells of knowledge and interesting characters. This is how I felt after my meeting with Bruce Morton, director of the environmental studies program at Goodwin College.

Meeting Bruce for the first time in a situation other than passing by, was a great experience. I had previously heard about this reserved and calculating professor at Goodwin from a colleague of mine at CT River Academy, which is the high school that is hosted by the college. I walked across campus and strode the stairs to his floor and scouted the room numbers until I found his office. At Goodwin College, the environmental studies department has a suite with about 6 or 8 offices with a common area. Bruce’s office was closest to the hallway. Once the meeting began, I briefly explained the project and my aspirations of publishing the finished product. Then, I shared about the angle and the happenstance meeting I had with the Vice President and what his expectations were (see previous post). After some time, I realized that although he might have limited knowledge about what I was looking for, he certainly had a lot of connections.

While I was sitting there, in his office, Bruce began picking up the phone and calling other professors and professionals that he knew in fields related to environmental studies, the CT River, and Goodwin College. The first person he called was a history professor at the College who seems to have a lot of information about what I am looking for and might be able to direct the approach to the project. In addition to this contact, Bruce sent an introductory email to four other people, including one from Riverfront recapture, which may also help with some work I am doing with CT Humanities. Overall, this was a productive meeting. I am just beginning to realize how important it is for public historians to engage in never-ending networking because you need to know people to get information. I guess the old adage is right…Sometimes it IS not what you know, but who you know.

Image Credits:

http://www.goodwin.edu/majors/bachelors/environmental_studies/

A Meeting by Happenstance

Last week, I ran into the Vice President of Goodwin College and we began discussing the progress of the land-use history I am working on for his organization. The meeting began with me asking if Goodwin College owned a piece of property in Wethersfield on the West bank of the Connecticut River known as Crow’s Point. I asked him this because there was an abundance of primary source documents in “the pile” of resources I have been combing through (This “pile” is his research on this project to date). He remarked that the college has owned the property since 2006 and that he would like this included in the land-use history. My first reaction was, “nice.” This property had some documentation about how the land was used, preserved and planned to be developed. I thought this would fit nicely into the Environmental History angle that I was working on. I figured that this would be a good time to bounce this angle off of him to see what came back. His response was a bit troublesome.

Although he did seem interested in the idea of how the land was used, abused, and renewed, the Vice President wanted the research to focus on the “interesting things” that have happened on the property. Then, I tried to explain that I would definitely include such information, but I was looking for an angle that would contribute to the field of history. I remarked, “I am looking for an angle that will appeal to a wider audience, something that may get published.” He responded that they will publish it and not to worry about it. By the way we were interacting, I could tell that I was talking to a history buff, not a historian. Then, I asked some clarifying questions that gave a refocus to my research. After this 4-5 minute meeting, I came to understand that they really wanted a chronology of the development of the land. They wanted some of the history of Pratt and Whitney and the development of the neighborhood pictured here that is adjacent to the Goodwin College Riverfront Campus. They want to know more about the ferry that Colt created to help his workers circumvent the tolls in and out of Hartford. They are seemingly less interested in the rejuvenation of the land that their riverfront campus occupies, although the do want some of this included. Overall, I am grateful for this meeting and the amount of research that the Vice President has put into this project.

Although he did seem interested in the idea of how the land was used, abused, and renewed, the Vice President wanted the research to focus on the “interesting things” that have happened on the property. Then, I tried to explain that I would definitely include such information, but I was looking for an angle that would contribute to the field of history. I remarked, “I am looking for an angle that will appeal to a wider audience, something that may get published.” He responded that they will publish it and not to worry about it. By the way we were interacting, I could tell that I was talking to a history buff, not a historian. Then, I asked some clarifying questions that gave a refocus to my research. After this 4-5 minute meeting, I came to understand that they really wanted a chronology of the development of the land. They wanted some of the history of Pratt and Whitney and the development of the neighborhood pictured here that is adjacent to the Goodwin College Riverfront Campus. They want to know more about the ferry that Colt created to help his workers circumvent the tolls in and out of Hartford. They are seemingly less interested in the rejuvenation of the land that their riverfront campus occupies, although the do want some of this included. Overall, I am grateful for this meeting and the amount of research that the Vice President has put into this project.

This happenstance meeting helps me in several ways. First, it helps to cut out some of the unnecessary research I was conducting about the floodplains near the Putnam Bridge. Next, it helps me refocus my attention to the development of the community just East of the campus. Finally, it helps me focus less on the remediation of the property, thus cutting out the last 5-8 years. This process is interesting because, if this were solely my own project, it would focus on the use, abuse, and renewal of the property, examining how and why this use has changed over time, and linking this change to broader themes within environmental history. I wouldn’t say that this project is any less valuable, just different. As a public historian, I guess it is not my place to place value on a project or its outcomes. The value of the project is set by the contracting party and I am not at liberty to share the “value” of this project.

The Pile

This week I met with my supervisor, Steve Armstrong, and we discussed the progress on the project so far. We went back and forward about what the overall goal of the Goodwin project and how we could make this topic relevant to a wider audience. Ultimately, we decided that an environmental history angle was appropriate for this type of project. I suggested we meet with Bruce Morton,an environmental studies professor that teaches at Goodwin College. From what I have heard from colleagues that have worked with him, or taken his classes, Professor Morton really knows his stuff when it comes to the connections to environment. I am currently in the process of setting up a meeting between Bruce Morton, Steve Armstrong and myself. In the meantime, I am sifting through “the pile.”

When I am referring to “the pile,” I am describing the pile of primary sources that I first came across in a meeting at Goodwin College. “The Pile” is a collection of maps, news articles, printed Google books, and legal documents. Most of the sources are available on the Internet, but there are also engineer’s maps and plans for a resort. One interesting source provided was a frame by frame printout of a 1640 map of Whethersfield, CT. Each frame was printed on a separate page, making interpretation almost impossible. I followed the url at the bottom of the page to a series of frames of this map. In order to get a good look at the map, I had to take a screen shot of each frame and then puzzle them together. Included here is a copy of the map, which shows the CT River before it shifted to its present course.

Resources:

Driftin’ w/ Wick

A few weeks back I had the honor and pleasure to meet with Wick Griswold, Sociologist at the University of Hartford. According to his page on the university website, Wick’s “favorite course to teach is the Sociology of the CT River Watershed.” Wick continues, “The mighty Connecticut River is a natural treasure. It’s history, ecology and beauty are sources of endless knowledge and aesthetics.” I decided to contact Prof. Griswold because of his newly released book, A History of the Connecticut River. Steve Armstrong and I met in his office on the university campus. This meeting was filled with energy, interest, and inquiry.

A few weeks back I had the honor and pleasure to meet with Wick Griswold, Sociologist at the University of Hartford. According to his page on the university website, Wick’s “favorite course to teach is the Sociology of the CT River Watershed.” Wick continues, “The mighty Connecticut River is a natural treasure. It’s history, ecology and beauty are sources of endless knowledge and aesthetics.” I decided to contact Prof. Griswold because of his newly released book, A History of the Connecticut River. Steve Armstrong and I met in his office on the university campus. This meeting was filled with energy, interest, and inquiry.

I originally contacted Wick looking for an angle for the Goodwin College project (see previous post). Following this meeting, I had just as many questions as I had answers, if not more. I think this is a good thing. As this meeting swirled in my head, I realized that his book was much more valuable than I previously thought. Mr. Griswold is more than a Sociologist, he is a living keeper of history. Wick is often found drifting down the CT River from the Enfield falls to the mouth of the CT River bordered by Old Saybrook and Old Lyme. According to our conversation and his book, the trip takes four days. Wick has a deep connection to the to the CT River and to its history.

Our meeting covered topics including the River Tribes of the lower Connecticut, changes in transportation and industry on the river,  and the effects of human-induced environmental decline on the region. Steve and I posed question after question trying to indicate the hook or angle for our research. By the time we left, Wick’s suggestion was that the angle was “the future.” When we left that day, we appreciated the help, but were not sure if this was the angle we were looking for. For instance, how could a historian base the hook or angle of their research on the future?!? However so much that this may seem absurd, there may be some credibility to his suggestion.

and the effects of human-induced environmental decline on the region. Steve and I posed question after question trying to indicate the hook or angle for our research. By the time we left, Wick’s suggestion was that the angle was “the future.” When we left that day, we appreciated the help, but were not sure if this was the angle we were looking for. For instance, how could a historian base the hook or angle of their research on the future?!? However so much that this may seem absurd, there may be some credibility to his suggestion.

The future of the CT River is one of reclamation and recovery. The angle for the Goodwin project just may be the environmental progress that has been made on the property. So, we could discuss the use, focusing on the detrimental effects of human environment interaction, and then explain how Goodwin in working to reclaim the land. All of this would be within the broader historical context of land-use. The more I think about this prospect, the better it sounds. There are only two obstacles to this “angle.” First, our client only wants the history of the land up until the time when the college moved to the area, so I have to make sure that this approach will fall into what they are asking for. The second obstacle is making sure that my project supervisor is on board. I have a meeting with Steve tomorrow, so I guess we will find out then.

Sources:

http://uhaweb.hartford.edu/griswold/

http://www.amazon.com/History-Connecticut-River-The-Press/dp/1609494059

Searching for an Angle

The biggest challenge for researching the land use history of Goodwin College’s River Campus is finding an interesting angle that would appeal to a broader audience than just the five or six people from the non-profit that contracted the assignment. Of course, the easiest thing to do is to research the records at the town hall and explain the chronology of how the land changed over time. Steve Armstrong, my supervisor for this internship, says that this is just not enough and I agree. We want to make this into a project that may have a possibility to be published. In order to do this, the interpretation of the campus’s history must be applicable to a wider historical context. This is the biggest roadblock to the research.

To begin this project, I acquired a map of the colleges holdings along the CT River. As you can see from this image, the Goodwin College campus is nestled along the Connecticut, which in itself is experiencing a resurgence in contemporary and historical interest. The map shows all of the land in East Hartford, Glastonbury, and Wethersfield that the college has acquired. My early research of the land use of this property indicates that most of the land was flood plains and meadows, with little economic development and limited written historical record. Some information I have uncovered from interviews of town historians and municipal bureaucrats shows that the most important development on the land is the introduction of coal depots and later home heating oil distribution centers in the 20th century. The land that the college and its myriad of magnet schools sits on is considered a brownfield because of all of the contamination from years of abuse and waste.

When I first began to research this project, I though it would be a compelling story to frame as sort of an environmental history. At first, I was thinking that it could be a story of human environment interaction, but my supervisor did not think this was appealing enough. Now, however, I am thinking that the angle might be environmental history. According to the surprisingly well researched and cited entry on Wikipedia, “Environmental historians study how humans both shape their environment and are shaped by it.” Honestly this is very similar to my first instinct with this project, but maybe this is the angle we are looking for. Environmental History took root in the environmentalist movement of the late 1960s and 1970s at the same time that land reclamation began on sites such as the Goodwin College River Campus. Maybe the connection to the broader history IS how people have interacted with the environment. I guess that is the nature of a land use history. The thesis must answer how people have shaped and been shaped by the environment. Is this really an enticing story?

The Search Continues…On to environmental history journals.

Resources:

- New England Real Estate Journal. “Goodwin College wins Blue Ribbon Award at The Real Estate Exchange Developer’s Showcase.” Accessed September 23, 2012. http://nerej.com/31424.

- Wikipedia. “Environmental History.” Accessed September 23, 2012. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Environmental_history.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment